“Clothespegs” by Otodo, licensed under Creative Commons. https://flic.kr/p/6rGPAg

In the original post and discussion which prompted me to create this blog, I felt the need to distance or separate the terms “postmodernism” and “poststructuralism” from a tactical viewpoint. Here I’ll try to explain why, and in so doing attempt to clarify some of the main strands of critical theory that my readings of the ELT industry draw upon – that’s to say, as much as clarification can be any use when dealing with thinking which tends to value opacity over transparency.

The words postmodern-ism/-ist, in conjunction with relativ-ism/-ist crop up frequently in Geoff Jordan’s and Kevin Gregg’s various defences of the rational basis of SLA theory against what Gregg calls “attacks from within the gates” (Gregg: 2000) – attacks which basically (and often clumsily) question the right of rational realism, or scientism, to be the only or most privileged way of accounting for second language acquisition. I would like to offer some thoughts on Gregg’s article in a future post. Compared with Gregg, Jordan’s approach is more considered and shows that he has read beyond the SLA version of “postmodernist” thinking, but I don’t think his conclusions differ too much from Gregg’s.

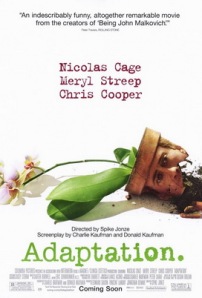

There, I did it again, putting “postmodernism” in inverted commas, those punctuational clothespegs we use to hang up soggy concepts, concepts we’re not happy about touching. Why? Because, for me, it’s less a way of thinking than a description of the state of things. While it is true that what can be called poststructuralist thinking emerged around the same time as the postmodern state of things began to become most visible, around the late 1950s/early 1960s, I don’t think either term is reducible to the other. So although there are those in SLA who have described their approaches as postmodernist, I’ll be using poststructuralist as an umbrella term covering several (and sometimes competing) theoretical approaches whose methodologies can be used to analyse not only postmodernity (as a description of a state of things) but any body of discourses in which there are questions of reference, representation, power and difference. Which is to say, from the poststructuralist perspective, any discourse at all.

Of course, there is a certain degree of slippage, or drippage from this most soggy of concepts, “postmodernism”, and it’s hard to avoid the backsplash. Jean-François Lyotard’s seminal The Postmodern Condition, a book whose position on science we will return to, may offer some kind of waterproof protection (another umbrella, perhaps). Lyotard shies away from attaching -ism or -ist to the root word of his enquiry except when referring to artistic movements, suggesting that there are certain types of creative activity which are consciously postmodern, are postmodernist, are consciously reacting against or going beyond modernism. “Postmodern” on the other hand, for Lyotard, applies to a cultural condition in which belief in the grand narratives or “metanarratives” of the enlightenment, sorely questioned during the modern period, have finally collapsed – a world in which plurality or eclecticism disrupts the idea of dominant ways of doing things, dominant styles:

Of course, there is a certain degree of slippage, or drippage from this most soggy of concepts, “postmodernism”, and it’s hard to avoid the backsplash. Jean-François Lyotard’s seminal The Postmodern Condition, a book whose position on science we will return to, may offer some kind of waterproof protection (another umbrella, perhaps). Lyotard shies away from attaching -ism or -ist to the root word of his enquiry except when referring to artistic movements, suggesting that there are certain types of creative activity which are consciously postmodern, are postmodernist, are consciously reacting against or going beyond modernism. “Postmodern” on the other hand, for Lyotard, applies to a cultural condition in which belief in the grand narratives or “metanarratives” of the enlightenment, sorely questioned during the modern period, have finally collapsed – a world in which plurality or eclecticism disrupts the idea of dominant ways of doing things, dominant styles:

Eclecticism is the degree zero of contemporary general culture: one listens to reggae, watches a western, eats McDonald’s food for lunch and local cuisine for dinner, wears Paris perfume in Tokyo and “retro” clothes in Hong Kong; knowledge is a matter for TV games. (Lyotard: 1984)

You’ll notice no websurfing – The Postmodern Condition was published in 1979, although it proved prescient in its prediction of massive public information storage and retrieval systems. But this description of the eclectic, decentred, playful postmodern subject, accurate though it may be when referring to the contemporary cultures of the world’s most “developed” societies – Lyotard’s explicit field of study – seems troublingly close to the ideal consumer-subject, plastic and malleable, of what has optimistically been referred to as “late capitalism” (see Jameson 1991). On the one hand, there is the political and ethical move that a postmodern culture offers – to suspect grand narratives, to create new, situated, unstable but potent interventions; and on the other is a postmodern identity very much at the service of the discourses of advanced consumerism (you are what you buy, for example). Advocates of a consciously performative vision of identity, such as Judith Butler, are in this sense politically suspect, open to the accusation of “late capitalist libertarian[ism]” (in Zizek’s phrase; Zizek 2007).

What are some of the hallmarks of this idea of postmodern culture, encompassing as it seems to do both radically radical and radically conformist positions? Aspects may include the dominance of the image, in advertising, entertainment, social and news media; a certain abandonment of cultural and political metaphors of depth and a consequent privileging of surface, of superficiality; a certain distancing, a renunciation of emotion and emotional response to art, culture or politics in favour of irony, the postmodern shrug, the one-liner; the repeated citation of other works, the celebration of intertextuality – not “quoted”, woven together by artistic genius as it may have been by a modernist, a Joyce or Eliot, for example, but “incorporate[d] into the very substance” of the work (Jameson 1991); the idea of self-referentiality, that representation is only ever about representation, from TV shows about TV shows to novels about novels to films about film; the collapse of the modernist distinction between “high” and “low” culture; and the coming to voice of previously subordinated identities, contradictorily coinciding with a persistent questioning of the stability of identity, of the possibility of an individual style, which in itself, according to Jameson, has led to the triumph of pastiche over parody.

What, then, is postmodernist critique, or postmodernist thought (two collocations, drip drip, that cannot be ignored) – is it to be defined as thinking/theorising about postmodernity, somehow outside it but observing it critically – or is it thinking which is postmodern in its nature, born from the condition of postmodernity and therefore slave to no grand narrative? I find this question too sticky; I find its undecidability unproductive. To add to my reluctance, there is the sense in which the word “postmodernist” itself has, at least in the hands of rationalism’s most vehement defenders, a pejorative import – that using it, whether in or out of clothespegs, carries with it an implicit mockery, a snigger behind the hand at the term’s contradictory anachronism (not helped when one considers those works which exhibit many of the key features of postmodernist art but predate the movement by sometimes hundreds of years – Sterne’s novel The Life and Opinions of Tristam Shandy, Gentleman (1759) being one obvious example).

There is, of course, this danger with “post-“anything, the seeming impossibility of the development of an idea whose definition places it after something else, with the only tactical options being to go back to what was there before the post-, or to post the post- itself, or to somehow accept that we’ve reached the end of history, at least in epistemological terms. My preference for “poststructuralism” does not escape these questions, cannot really be fully and satisfactorily separated from “postmodernism” on the conceptual washing line, but its history as a way of thinking rather than a set of general cultural conditions, or a mode of representation of those conditions, make it seem far more useful to me in my present task.

Structuralism is a theoretical paradigm first emerging at the beginning of the 20th Century in the field of linguistics (with Ferdinand de Saussure) and later gaining currency, at least up to the 1970s, in literary and cultural theory, anthropology and sociology. It advocated a mode of analysis which considered meaning as dependent on an overarching structure, often regarded as fairly static. Within this structure culture becomes intelligible. Roland Barthes’ analysis of James Bond stories, for example, sought to identify the elements particular to Bond narratives, and by extension, all narratives – in mapping out a grammar of narrative structure, Barthes put forward the idea of a narrative code, the understanding and acceptance of which by a reader is essential to understanding the story itself.

Speaking very broadly, structuralism’s emphasis on systems of signs as the source and condition of any meaning, of the idea of human culture as fundamentally coded, rang true with some of the intellectuals caught up in the revolutionary atmosphere of late 1960s Paris, but its ahistoricism and tendencies towards totalisation, hierarchisation and what Derrida called its need not only to suspect, but “to reduce and to suspect” (Derrida: 1967), did not. For Barthes, on the one hand:

One of structuralism’s main preoccupations [is] to control the infinite variety of speech acts by attempting to describe the language or langue from which they originate, and from which they can be derived[.] Faced with an infinite number of narratives and the many standpoints from which they can be considered (historical, psychological, sociological, ethnological, aesthetic, etc.), the analyst is roughly in the same situation as Saussure, who was faced with desultory fragments of language, seeking to extract, from the apparent anarchy of messages, a classifying principle and a central vantage point for his description. (Barthes 1975)

For Derrida and others, however, the impossibility of definitively reducing the “infinite variety of speech acts” became the starting point for poststructuralism, a more radical force in critical theory insofar as it refuses the idea of a dominant structure that cannot in its own terms be deconstructed, that cannot escape its own history or suppression of history, that cannot unequivocally posit itself as a universal structure with a defining and delimiting “central vantage point” that somehow stands outside that structure, that escapes structurality. This, for Derrida, constituted a rupture, a moment

in which language invaded the universal problematic; that in which, in the absence of a center or origin, everything became discourse – provided we can agree on this word – that is to say, when everything became a system where the central signified, the original or transcendental signified, is never absolutely present outside a system of differences. The absence of the transcendental signified extends the domain and the interplay of signification ad infinitum. (Derrida 1978)*

In the case of Michel Foucault, one can trace this rupture in the trajectory of his works, from the more strictly structuralist perspective of The Order of Things and The Birth of the Clinic to a mode of historical critique more focused on conceptual instability, on the idea of power and knowledge as both produced and productive, but above all situated and contingent. In this way, although Foucault resisted the term poststructuralism, there is a movement in his work which breaches the totalising concept of structure, and that allows me to bring Foucault and others together with Derrida under the umbrella of poststructuralism without reducing the critical tensions between them. Zizek, to whom I referred earlier, is another example of an unlikely umbrella-sharer – a Marxist (or postmarxist?) thinker who at once resists the poststructuralist insistence on the dissolution of stable subjectivity and at the same time adopts some of poststructuralism’s more recognisable moves in order to do so.

I will suspend any discussion of what these moves may be for now – Patrick Amon has already elucidated a key example in his first comment on the previous post. I would rather, in the next one, turn more firmly towards the ostensible object of study for this blog – the ELT industry – and show the moves by attempting to deploy them. I have always felt that there is no poststructuralism outside of poststructuralist readings, no deconstruction outside of doing deconstruction, so from now on I will abandon this unavoidably reductive attempt at overview and proceed, as best I can, with the business at hand. Just don’t call me a postmodernist – or even a “postmodernist”.

*EDIT: Just to complicate the chronology of structuralism/poststructuralism I have offered, the rupturing “event” to which Derrida refers in the history of the concept of structure is not easily identified as the historical moment of rupture which produced poststructuralism, in a linear sense, as something which follows structuralism, whose centre could not hold. Derrida goes on to cite three great masters of suspicion regarding centred structures, Nietzsche, Freud and Heidegger, whose names, along with that of Marx, should never be omitted from any account of the development of poststructuralism – and whose ghostly presences call into question the “post-” of that formation.

References

Barthes, Roland and Lionel Duisit. 1975. “An Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives”. New Literary History Vol. 6, No. 2

Derrida, Jacques. 1978. “Structure, sign and play in the discourse of the human sciences”. Writing and difference. Trans. Alan Bass. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Gregg, Kevin. 2000. “A theory for every occasion: postmodernism and SLA”, Second Language Research 16

Jameson, Frederic. 1991. Postmodernism, or the cultural logic of late capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press

Lyotard, Jean-François. 1984. The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge. Trans. Geoff Bennington and Brian Massumi. Manchester: Manchester University Press

Zizek, Slavoj and Michael Hausser. 2007. “Humanism is not enough.” IJBS. Vol. 3, No. 3

Hi Neill,

Very interesting, well-written discussion if I may say so. Below, a few comments on post-modernism, lazily cut-and-pasted from Jordan, 2004.

Derrida thinks that scientific texts should be treated like any others, and that it is important to reject the special privileged status of scientific discourse. Not surprisingly, then, he also thinks that literary scholars trained in deconstruction are capable of a more profound understanding of scientific texts than scientists themselves, an understanding that uncovers the “real” meaning and the unconscious intentions of the writers. At the same time, Derrida, like many postmodernists, claims to be quite familiar with science, and is not averse to using some of its findings to support his own point of view. Here’s an example:

“The Einsteinian constant is not a constant, not a center. It is the very concept of variability – it is, finally, the concept of the game. In other words, it is not the concept of some thing – of a center from which an observer could master the field – but the very concept of the game”. (Derrida, 1981, cited in Gross and Levitt, 1998: 79) The “Einsteinian constant” is, of course c, the speed of light in vacuo, roughly 300 million meters per second. As Gross and Levitt say, physicists are not likely to be impressed by such verbiage, and are hardly apt to revise their thinking about the constancy of c.

More generally, the post-modernists and constructivists obviously have a point when they say (not that they said it first) that science is a social construct. Science is certainly a social institution, and scientists’ goals, their criteria, their decisions and achievements are historically and socially influenced. And all the terms that scientists use like “test”, “hypothesis”, “findings”, etc., are invented and given meaning through social interaction. Of course. But, and here is the crux, this does not make the results of social interaction an arbitrary consequence of it. As Bunge (1996) points out “The only genuine social constructions are the exceedingly uncommon scientific forgeries committed by a team.” (Bunge, 1996: 104) Bunge gives the example of the Piltdown man that was “discovered” by two pranksters in 1912, authenticated by many experts, and unmasked as a fake in 1950. According to the existence criterion of constructivism-relativism, we should admit that the Piltdown man did exist – at least between 1912 and 1950 – just because the scientific community believed in it (Bunge, 1996: 105).

The post-modernists confuse two separate issues: claims about the existence or non-existence of particular things, facts and events, and claims about how one arrives at beliefs and opinions. To take the example of the Piltdown Man hoax, whether or not he is a million years old is a question of fact. What the scientific community thought about the skull it examined in 1912 is also a question of fact. When we ask what led that community to believe in the hoax, we are looking for an explanation of a social phenomena, and that is a separate issue. Just because for forty years the Piltdown man was supposed to be a million years old does not make him so, however interesting the fact that so many people believed it might be.

As Paul Boghossian points out, the class of things that can be labelled social constructions is enormous: nation states, the dollar, university education and the BBC are random examples. Anything that could not have existed without societies actually defines the class, and likewise, anything that actually does or did exist independently of societies cannot be a social construction, dinosaurs, giraffes and proteins are examples. “How could they have been socially constructed, if they existed before societies did?” (Boghossian, 2001: 7) Yet it is precisely this obvious distinction that is ignored in many post-modernist texts, which claim that our beliefs are all we have, and that there is nothing “out there” that exists independently of them. While it might very well be the case that we believe that dinosaurs existed, and that DNA exists today because the scientists tell us so, it remains, at least for those of us who want to take a rationalist view of the world, an independent question of fact as to whether or not such things exist, i.e. whether or not our beliefs are true or false.

When post-modernists say that there are multiple, often conflicting views of the world, that they are all (at least potentially) meaningful, and that the question of which views are true is socio-historically relative, this is a perfectly acceptable comment, as far as it goes. If the argument is that the observer cannot be neatly disentangled from the observed in the activity of inquiry, then again the point can be well taken. But when post-modernists and constructivists insist that empirical evidence exists exclusively in the minds of individuals, that there is no “objective” world, and that “what can be known and the individual who comes to know it are fused into a coherent whole”, then they have disappeared into a Humpty Dumpty world where anything can mean whatever anybody wants it to mean.

It is when postmodernists insist on a radically relativist epistemology, when they rule out the possibility of data collection, of empirical tests, of any rational criterion for judging between rival explanations that I believe we rationalists should part company with them: solipsism and science (like solipsism and anything else of course) do not go well together. If postmodernists reject any understanding of time because “the modern understanding of time controls and measures individuals”; if they argue that no theory is more correct than any other; if they believe that “everything has already happened”, that “there is no real world”, that “we can never really know anything”, then I think they should continue their “game”, as they call it, in their own way, and let those of us who prefer to work with more rationalist assumptions get on with scientific research.

Boghossian, P. 2001: What is social construction? Times Literary Supplement,

February 23, 6-8.

Bunge, M. 1996: In Praise of Intolerance to Charlatanism in Academia. In Gross, R, Levitt, N., and Lewis, M. “The Flight From Science and Reason”. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, Vol. 777, 96-116.

Gross, P. and Levitt, N. (1998) “Higher Superstition”. Baltimore: John Hopkins University

Press.

Jordan, G. (2004) “Theory Construction in SLA”. Amsterman, Benjamins.

LikeLike

Thanks Geoff – your cut’n’paste may be lazy but adds some welcome context to the discussion, especially for those not familiar with your book (or Gross’ and Levitt’s) or the extracts published on your blog. I’d just like to add some comments, if I may.

In terms of the “science wars”, the name attached to the debate between poststructural thinking and scientific realism which took place in the mid 90s, I have always found it interesting that so much of the attack from the science camp was focused on Derrida rather than Lyotard. A look at Derrida’s oeuvre quickly shows that he favoured readings of philosophy, literature and political discourse and very rarely made any pronouncements on science, aside from the occasional allusion, such as the one quoted by Gross and Levitt., and never (to my knowledge) offered an extended reading of any scientific text. Lyotard, on the other hand. dedicated an entire book (The Postmodern Condition) to the status of science in an age of crumbling certainties – so why is it Derrida who gets singled out?

Arkady Plotnitsky, referring to the comment on the Einsteinian constant cited by Gross and Levitt, points out that it is remarkable, “even given Derrida’s status as an icon of intellectual controversy […] that out of thousands of pages of Derrida’s published works, a single extemporaneous remark on relativity made in 1966 (before Derrida was ‘the Derrida’ […]) in response to a question by […] Jean Hyppolite, is made to stand for nearly all of deconstructive or even postmodernist (not a term easily, if at all, applicable to Derrida) treatments of science”. (Plotnitsky 1997) He goes on to contextualise Derrida’s remarks to Hyppolite in terms of the text to which the comments referred (Derrida’s own “Structure, sign and play”, as cited above) and offers a reading of his reference to Einstein which differs significantly from that of Gross and Levitt. The point is that Gross and Levitt grossly neglected the text around Derrida’s remark and made no effort to explore what Derrida meant by “center” and “game”, concepts discussed in “Structure, Sign and Play” and whose understanding may have permitted a reading similar to Plotnitsky’s.

I really do not know exactly which poststructuralist thinker has either claimed that there is “nothing out there that exists independently of them”, or has seriously challenged the validity of data collection or of empirical tests in scientific enquiry – I’m not saying no one ever has, but I’m not aware of it, not even in Lyotard’s book. Quite rightly, however, any deconstructive reading of those discourses in which data and tests are explained, read, justified, offered as proof, and defended as rational, which does not adequately understand the terms in which scientific statements are made or defended, could be regarded as at best partial and at worst ignorant. The same standards must apply to readings of deconstructive texts by the scientific community.

Finally, what interests me here is where SLA might fit into the “science wars” – doesn’t SLA, like all the human sciences, have battles of its own in regard to its scientific status? That is, quite aside from the “postmodernists”, are there not those in the natural sciences who would deny SLA the privileged status of scientific discourse, that is, as a discourse which can adequately access and explain the reality of second language acquisition in scientific terms?

Plotnitsky, Arkady. “‘But it is above all not true’: Derrida, relativity and the ‘science wars'”. Postmodern Culture, Vol. 7 No. 2

LikeLike

Hi Neil,

A few points:

1. That Derrida’s remark about the Einsteinian constant can’t be taken as representative of his work or of post-modernist views on science is pretty obvious. That giving the quote a wider context makes it any less ridiculous is less obvious. Here’s the link to Plotnitsky’s paper: http://pmc.iath.virginia.edu/text-only/issue.197/plotnitsky.197 . Readers can go to point 17 where Plotnitsky finally offers an alternative reading of Derrida’s remark and judge for themselves. The article is, IMHO, a good example of the over-worked, endlessly-repetitive, mind-numbing style adopted by post-modernists, following a long French intellectual tradition of never saying anything in 10 words where 100 will do.

2. A raft of post-modernists, including Derrida, Baudrillard, and Lyotard, plus Woolgar, Shawver, Ashley, Rosenau, Culler, Appignanesi and Latour (who said “There is no final meaning for any particular sign, no notion of unitary sense of text, no interpretation can be regarded as superior to any other”) all challenge the validity of data collection and of empirical tests in scientific enquiry.

3. I don’t understand the second half of paragraph 4 above, beginning “Quite rightly…”.

4. There are indeed those who would deny theories of SLA “the privileged status of scientific discourse”, Popper, Lakatos, Chomsky and Couvalis, among them. I personally agree with Feyerabend that Popper’s demarcation line is both absurd and unnecessary. I also think that in studying SLA, being “scientific” doesn’t matter at all. What’s important (here comes another cut and paste job!) is to adopt a realist epistemology which assumes that an external world exists independently of our perceptions of it and that it is possible to study different phenomena in this world, to make meaningful statements about them, and to improve our knowledge of them. This amounts to a minimally realist epistemology, and therefore excludes those who claim that there is no objective way to judge among competing theories.

Best,

Geoff

LikeLike

Fascinating discussion and fascinating follow-up comments. I’d like to make two remarks.

1. Thanks, Neil, for clarifying some useful distinctions and for reminding us of what Lyotard meant by the ‘postmodern.’ A much needed corrective to the mindless bandying about of this term.

and

2. To defend Derrida a bit, which isn’t like me, I think his remarks about the status of the constant c are fairly unobjectionable. His language is certainly less than transparent (but then it would be, wouldn’t it, given his attitude to language and the transparency thereof?) but when he talks of a ‘game’ he is doing so, I think, in much the same spirit as that in which the later Wittgenstein would refer to ‘a language game,’ by which, I think, Wittgenstein must mean that our various communicative and theoretical practices are indeed practices, and that as such they have some of the key characteristics of games, such as that they consist of ‘moves’ which may be legitimate or otherwise according to the rules of the ‘game’. Any proposal in theoretical physics is a ‘move’ which is constrained by these considerations of legitimacy (e.g logic and previous findings and the interpretation of those previous findings, itself constrained by logic and the interpretations of findings previous still and so on (there are infinite regresses here, obviously, but still we go on because go on we must.)). Some of these moves, such as the willingness to abandon Euclid’s parallel postulate (please don’t ask me to explain this), are especially bold, but still, to gain acceptance they must demonstrate an adherence to the rules shared amongst the physics community, or at least demonstrate that if they appear to break the rules the only alternatives would constitute a more egregious break. When Derrida says that c is ‘the concept of the game’ he must mean that Einstein has succeeded in precipitating a scientific revolution such that, now, c is at the centre of what Kuhn would call a ‘paradigm,’ that the new rules are such that any new proposal must demonstrate its consistency with the constancy of the speed of light, that Einstein’s proposal was not merely a move in the game but is now constitutive of the rules of that game. None of this, I think, requires physicists to revise their thinking about the constancy of c, so it is a false dilemma to imply that either they are right or Derrida is right and not both. The view expressed in Derrida’s remarks about c need not be inconsistent with the implicit understanding of physicists who continue to undertake research that is intelligible only on the view that the speed of light is constant. Nothing in Derrida’s remarks here, I think, implies that the speed of light is not constant. His remarks, rather, I think, confine themselves to the nature of scientific practice, and make no claims about the truth or otherwise of the findings achieved by the pursuit of that practice (elsewhere, he, or not even he so much as the countless people who invoke his name in support of a vacuous relativism that cannot fail to collapse into solipsism, do make that mistake, and they. absolutely, on pain of abandoning public rationality altogether, must be resisted.) I think though that Quine, a self-described amateur scientist, and Kuhn, a physicist, if I recall, before he became an intellectual historian, would be unperturbed by Derrida’s observations here. Bernard Derrida, I believe, Is Jacques’s nephew. I’d love to hear what he thinks.

LikeLike

I came back here to mention an interesting recent article that’s sort of relevant, but let me just say that I enjoyed Patrick’s comment, which is tempting to reply to. 🙂

To the issue, then. The latest issue of the SSLA journal has an unusual article (unusual because there are 9 co-authors) which addresses the on-going “science war” among researchers in SLA. It starts:

For some, research in learning and teaching of a second language (L2)

runs the risk of disintegrating into irreconcilable approaches to

L2 learning and use. On the one side, we find researchers investigating

linguistic-cognitive issues, often using quantitative research methods

including inferential statistics; on the other side, we find researchers

working on the basis of sociocultural or sociocognitive views, often

using qualitative research methods including case studies and

ethnography. Is there a gap in research in L2 learning and teaching?….

It comprises nine single-authored pieces, with an introduction

and a conclusion by the coeditors. Our overarching goals are (a) to raise

awareness of the limitations of addressing only the cognitive or only

the social in research on L2 learning and teaching and (b) to explore

ways of bridging and/or productively appreciating the cognitive-

social gap in research.

http://journals.cambridge.org/action/displayAbstract?fromPage=online&aid=9319228&fulltextType=RA&fileId=S0272263114000035

LikeLike

Hi Geoff and Patrick, and thanks again for your further comments. I’d love to read that article Geoff, attempts at rapprochement of this kind can only be welcome. Unfortunately, as a non- or ex-academic I am unable to read it unless I fork out €30 (or €4.49 for a rental – it would then have to be a toss-up between Cambridge Journals and the iTunes Store to decide this weekend’s entertainment). Can we look forward to a summary/critique on your blog?

To respond to Geoff’s initial points, and in some sense to Patrick’s too:

1. Your discomfort at Plotnitsky’s style does not preclude an admission that he, like Patrick, has offered an alternative reading. Two readings which take Derrida’s use of certain concepts into account, as well as the wider context of what were off-the-cuff remarks, something not done by Gross and Levitt. I accept there are too many examples of discourse in this field that border on babble to the detriment of rigorous argument. However, contrary to your perception of poststructuralism, I would venture that it’s possible to say that one of these readings is better than the others – my ignorance of some of the concepts and references in Patrick’s account, however, makes me hesitate to do so. I would say, however, that Gross and Levitt’s reading appears to me the worst, the most shallow and the least rigorous of the three, and above all the least responsible.

2. I am not familiar with all the names you mention so I will not attempt to respond in full. I’ll let Derrida speak for himself: “What is called ‘objectivity’, scientific for instance (in which I firmly believe, in a given situation), imposes itself only within a context which is extremely vast, old, powerfully established, stabilized or rooted in a network of conventions (for instance those of language) and yet which still remains a context. And the emergence of the value of objectivity (and hence of so many others) also belongs to a context. We can call ‘context’ the entire ‘real-history-of-the-world,’ if you like, in which this value of objectivity and, even more broadly, that of truth (etc.) have taken on meaning and imposed themselves. That does not in the slightest discredit them. In the name of what, of which other ‘truth,’ moreover, would it? One of the definitions of what is called deconstruction would be the effort to take this limitless context into account, to pay the sharpest and broadest attention possible to context, and thus to an incessant movement of recontextualization. The phrase which for some has become a sort of slogan, in general so badly understood, of deconstruction (‘there is nothing outside the text’ [il n’y a pas de hors-texte]) means nothing else: there is nothing outside context. In this form, which says exactly the same thing, the formula would doubtless have been less shocking. I am not certain that it would have provided more to think about.” (Limited Inc., a b c, p. 136)

Statements like Latour’s (“There is no final meaning for any particular sign, no notion of unitary sense of text, no interpretation can be regarded as superior to any other”) are therefore difficult to say anything about outside of their context, although I’d say that in the context of poststructural thought, or the hack-job end of it, ideas like this are tossed around too frequently. Latour seems to be invoking the concept of radical freeplay, which for Derrida can never be as “complete” as Latour suggests; for Derrida, “there can be no ‘completeness’ where freeplay is concerned. Greatly overestimated in my texts in the United States, this notion of ‘freeplay’ is an inadequate translation of the lexical network connected to the word jeu, which I used in my first texts, but sparingly and in a highly defined manner.” (Limited Inc, 115-6)

Is there a necessary and prohibitive contradiction in the idea that scientific enquiry operates in a context, on which it depends for its notion of truth or objectivity, and the simultaneous (if provisional) acceptance of that context, and with it scientific truth or objectivity? To give an analogous example, when our students do official speaking exams, I don’t think any of us sincerely believe the results are purely objective, but many of us accept that they are sufficiently or acceptably objective within the context of international speaking exams and the institutions and procedures which organise them, and in the wider contexts of work/education in which they are required as objective proof of language level. Science needs to be far more rigorous than a speaking exam, but not to the point of exceeding its context and claiming some kind of absolute position (but I’m pretty sure you already agree with this). Moreover, it is open to recontextualisation, or at least an attempt at it, the results of which (so far) haven’t been too pretty. But my point is that believing that something like scientific discourse can be recontextualised does not in itself amount to a rejection or devaluation of scientific knowledge, or the methods used to produce it.

3. I was just trying to say that both postructuralist/philosophical and scientific discourse need to hold themselves up to the standards of academic rigour enshrined in both their respective contexts (setting aside the fact that poststructuralism is still viewed as a contamination of philosophy). no more so than when one provides a reading of the other.

4. I understand your position, but if SLA theory is not science, does it necessarily need to be analogous to science, that is, to operate in an analogous way? Can’t it, shouldn’t it, doesn’t it already admit, or attempt to enter dialogue with, the so-called “alternatives” and properly recontextualise the field?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Neil,

About the article in SSLA, I forget that so many people have to pay daft sums of money to read articles from journals. It’s worth reminding people that If you live in the UK, a local library will get you copies of articles from academic journals, and that abroad most local universities will look kindly on polite requests. Anyway, I’ll put a summary of the cited article on my blog.

Answers to your points.

1. I agree that the importance of Derrida’s remark about the speed of light has been exaggerated, and I think it was lazy of me to have used it as evidence. But the remark cannot be rescued by a wider context or “re-interpretation”: it’s rubbish.

2. If you adopt a realist ontology and epistemology then you reject the context specificity of truth and objectivity. I, like most rationalists, adopt a correspondence theory of truth, and agree with Popper that causal theories can’t be proved true, they can only be falsified. As for objectivity, I again agree with Popper’s view that whatever motives scientists had for doing what they did, and taking the decisions they did, they gave us theories, and this is the basis of objective knowledge, what Popper refers to as “World Three”:

“We may distinguish the following three worlds or universes: first the world of physical objects or of physical states; secondly the world of states of consciousness, or of mental states, or perhaps of behavioural dispositions to act; and thirdly, the world of objective contents of thought” (Popper, 1972: 106).

Popper develops this idea:

In our attempts to solve problems we may invent new theories. These theories are produced by us; they are the product of our critical and creative thinking, in which we are greatly helped by other existing third-world theories. Yet the moment we have produced these theories, they create new, unintended and unexpected problems, autonomous problems, problems to be discovered. This explains why the third world which, in its origin, is our product, is autonomous in what may be called its ontological status. It explains why we can act upon it, and add to it or help its growth, even though there is no man who can master even a small corner of this world” (Popper, 1972: 161).

3. All theories go through a constant process of evaluation, modification and re-formulation, but this doesn’t amount to re-contextualisation. You use this idea of re-contextualisation throughout, but theories, including those in SLA, often claim to apply universally: “there is a critical period for SLA”, for example. In all these cases, contextualisation (and re-contextualisation!) are not required. Similarly, discussions which seeks to explain phenomena by appeal to logic, rational argument and empirical evidence don’t need to be held in different “contexts”.

4. Research into SLA can, in my opinion take absolutely any approach it likes. Researchers can articulate a hypothesis which is then tested by carefully-controlled experiments using quantitative methods, or they can adopt “ethnographic” approaches,collecting “rich” qualitative data any way they like, or they can lie on a bed, smoke opium and wait for a visit from the muse, What’s important is that the explanation that emerges is articulated in such a way that its claims use clearly-defined terms, are logically consistent, and have empirical content.

Best,

Geoff

Popper, K. R. (1972) “Objective Knowledge”. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

LikeLike

Hi Geoff

Thanks for clarifying your position – I think the idea that one can leave context out of it is probably where you and I differ the most. Anyway, I certainly didn’t intend to conflate reformulation and recontextualisation – I accept they are not the same thing.

I’ll look forward to that summary then!

Cheers

LikeLike

This is fascinating. I’m very glad you decided to start a blog, Neil. I doubt I’ll be contributing much, but I am likely to benefit a lot from reading it as I embark on the next stage of my EdD, which is on education futures. You said in your first post Neil that your academic background was all about postructuralism, and you were then surprised by the prevalence of humanism when you joined the ELT “community”. I’ve had the opposite experience, in that I did my masters at Edinburgh, where Chomskyan linguistics and communicative competence were the order of the day. The legacy of Corder and Halliday was all over the place. Only now, as I study education at doctoral level, am I encountering all this discourse on postmodernism.

I’d like to ask a couple of questions, if I may. They may seem naive and obvious to those readers who already know a lot about the subject, and at the same time they may not be easy to answer quickly, so feel free to ignore them for either of these reasons.

1. It appears that postmodernism and humanism are in conflict with each other. How is this? Is there not something quite similar about a school of thought that values the subjective and another that values the individual? Am I missing something important?

2. Does postmodernism lead us to a situation where formal education has no more validity than no education at all?

3. With regard to language teaching, Kumaravadivelu (TESOL Quarterly 1994, 28/1) described the “Postmethod Condition”. Is this equivalent to a postmodern condition?

Thanks again for starting this – I’m keen to know where it leads and I hope I manage to keep up!

Steve

LikeLike

Hi Steve and thanks for the comments. Please don’t apologise, I welcome any genuine questions, but I don’t want to give the impression that I am any kind of “expert” on this. You’ll know a lot more about some of the topics I hope to broach in coming posts …

1. I wouldn’t say there’s a specific conflict between “postmodernism” and humanism in the way we’ve talked about “postmodernism” vs science/SLA. Equally, there are plenty challenges to humanism from within ELT. Anyway, the major difference would probably be in the conception of subjectivity: Humanism seems to partly develop from existential notions of alienation, with the task of humanist psychology being to restore the subject to him/herself, to value the whole self or to help the subject achieve autonomy and wholeness. Poststructuralism emphasises the difference at the heart of identity, it claims that the wholeness that we perceive or strive for in our identities is ideological or illusory. Subjectivity in poststructuralism is therefore fractured or multiple and never autonomous from the discourses which produce it.

2. I don’t think postmodernism leads us anywhere, insofar as it’s a description of the late-capitalist state of things. Wooly “postmodernist” thinking may lead us there, irresponsible or absolute relativism, which might say that teaching creationism is as valid as teaching evolution (see e.g. http://clubtroppo.com.au/2012/02/22/george-bush-bruno-latour-and-the-end-of-postmodernism/). Extend that and you indeed have an argument that fits what you say, but then you’d have an “anything goes” argument that fitted absolutely … anything. I would just ask – is there such a thing as “no education at all”?

Poststructuralism as a theory/philosophy was born in formal educational settings, and while it challenges the structure and practices of those settings, I don’t believe it has any interest in doing away with them or recommending that no one needs them! Derrida was a renowned advocate for the inclusion of philosophy in primary schools.

3. I think I’ve read that article and it struck me at the time that the title was an obvious allusion to Lyotard. I’d need to go back and re-read it though. It certainly seems to be a postmodern type of concept, so rather than say it was “equivalent” to the postmodern condition, I’d say it was symptomatic of it (again regarding the postmodern as a general state of things). But I will find and re-read.

Hope this helps – please keep us up to date on the reading you’re doing, I am fairly ignorant of how all this theory plays out in the general education field.

LikeLike

Correspondence theories of truth are typically contrasted with coherentist theories of truth. This contrast is misleading, in my view, in that it encourages the idea that an account of truth that acknowledges the role of a system’s coherence in the production of that truth is somehow opposed to the common-sense notion that there is a correspondence between a true sentence and the state of affairs which it describes and that this correspondence is precisely what makes the sentence true. I’m interested to know, Geoff (sorry, Neil, but I’ll try and keep it brief), for the sake of clarification, when you say you adopt a correspondence theory of truth, do you mean that you adopt a theory (as I do, and as does, I’m fairly sure, Popper) according to which a statement may be sensibly said to be true but in which it is also accepted that that truth is only made possible by the sentence in question’s relations with other sentences, actual and possible, within the conventions of discourse within which the sentence is to be found meaningful, or do you mean that you adopt a theory (flat out bonkers in my view) according to which a statement is true because it simply mysteriously “corresponds” to something “out there” without any dependence on any wider system of signification at all? I really only am asking for the sake of clarification. To me it’s obvious that you mean the former since nobody sane ever meant the latter. The reason, though, that I think clarification is important is that I think a lot of people in the post-structuralist tradition take ‘a correspondence theory of truth’ to mean the latter view – that’s the straw man they’re always shooting at. We, though, of a more realist bent, should acknowledge that if by ‘a correspondence theory of truth’ we mean the former view then the Derridan questions about meaning, which aren’t, after all, so different from the Quinean questions, though Quine prefers to leave Nietzsche and Freud out of it, can’t, it seems to me, be prevented from arising.

LikeLike

Thanks Patrick, I’ll keep out of this as you’ve addressed it to Geoff. I just want to add that for me, the ideas of “anything goes” relativism and “humpty-dumptyism” are also straw men, the ones the scientific rationalism side like firing at. Unfortunately some on the “pomo” side tend to give the straw substance at times …

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Patrick,

I shouldn’t have mentioned the correspondence theory of truth because to make it “interesting” requires a lot of very technical stuff – including contributions by Wittgenstein, Russell and others among the logical positivists, until it was “rescued” by Tarski and others. Popper refused to really go into it much, preferring to talk about ‘truthlikeness’ or ‘verisimilitude’. So let me just say that I was referring, as you indicate, to correspondence in the Tarskian sense, where the definition of the truth of propositions in the object language (any natural language) is given in a formal or meta language. Sorry, Neil, back to you 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Geoff. My ignorance of Tarski is total. I’m very interested, though. Do his (her? Like I said, total) make Quine’s observations irrelevant? If so, do they also make Derrida’s arguments irrelevant?

LikeLike

Sorry. Not a full sentence there.

LikeLike

Neil

I’m finding this exchange of views very stimulating. Supposing it goes on I think you should think about making a book out of it. Obviously the title would be up to you but I’d like to suggest ‘Unlimited Ink.’

Best Regards

Patrick

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can I also take the time to agree with you, Geoff, that Popper and Eccles’s distinction between worlds 1, 2 and 3 is an extremely useful way of thinking about this stuff. The Self and It’s Brain is, among other things, a very moving, beautiful book.

LikeLike

And a wrong apostrophe. It just never ends.

LikeLike

Hi Patrick,,

I feel bad about hijacking Neil’s blog, tho I’m sure he won’t mind.

Yes, Tarski sorted out Quine! Tarski and Quine worked together at some big USA university. Tarski (like many) was trying to deal with all the problems created by the Vienna Circle (Schlick, Carnap, Godel, Russell, Whitehead, and Wittgenstein among others) although the epistemological issues go back to Plato. One big issue was antimonies or paradoxes (e.g. “I am a liar; I never tell the truth”) in language. Tarski suggested using a metalanguage to refer to statements in the object language. Very nifty, but all very techy. Enough!

LikeLiked by 2 people